Woke Obsessions

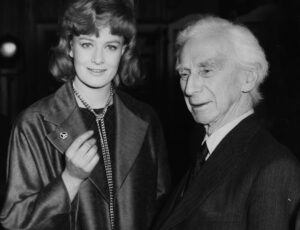

In the fall of 1950, a 17-year-old transfer student from the San Fernando Valley, already noted among her classmates for both her deep intelligence and her striking beauty, sat in on a sociology lecture at the University of Chicago taught by a 28-year-old professor born and raised in the slums across town. Ten days later, they were married, and after less than two years together, their only child was born. The troubled marriage of Susan Sontag and Philip Rieff would not last, and while Rieff’s intellectual accomplishments were considerable, both Sontag’s own achievements and her fame would dramatically outpace his. Beginning with the 1964 publication of “Notes on ‘Camp’” in Partisan Review and continuing for the rest of her life, she would gain international recognition as one of the most influential cultural critics of her era. Sontag died of leukemia in 2004 and Rieff of heart failure two years later; their son David, now 73, remains an active and prolific critic in his own right.

David Rieff’s career spans continents and decades. It has taken him to war zones and refugee camps from Bosnia to Rwanda to Afghanistan to Ukraine, far removed from the privileged Manhattan literary life he has enjoyed as a birthright. He has authored more than a dozen books, on topics ranging from humanitarianism to immigration to historical memory to mortality, and his words have appeared in seemingly every reputable publication in the Western world. Though his parents’ formidable reputations are an inextricable part of his story, Rieff is too erudite, too learned, and too polymathic to be dismissed as an intellectual nepo baby. He has distinguished himself as a voice of conscience confronting the post-Cold War world’s atrocities. It was at his urging that Sontag visited besieged Sarajevo in 1993, where she famously staged a production of Waiting for Godot.

But something has happened to David Rieff. His most recent book, Desire and Fate, was published by the niche British imprint Eris in the same month that Donald Trump defeated Kamala Harris. It’s a disorganized collection of short essays, all adapted from the Substack Rieff maintained from 2021 to 2024, that amount to an extended rant against the scourge of “woke” on the eve of the Trump administration’s kulturkampf against Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) policies. “It should be obvious by now that the DEI statements that are increasingly required at the meetings of professional associations are the functional equivalent of the loyalty oaths of the 1950s,” he writes in a typical passage, before going on to compare DEI bureaucrats to “the morals police in places like Iran.”

Though hailed by Lee Siegel in The New Statesman as “the profoundest reflection on woke culture yet to appear” and by Susan Neiman in The New York Review of Books as “a valuable tool” in strengthening “a movement that disentangles left from woke,” Desire and Fate is probably better understood as the lament of a writer and thinker who feels exasperated by the state of the culture in which his mother, her many legendary acquaintances, and he himself once flourished. The language of Desire and Fate may resonate with highbrow liberal writers like David A. Bell and Michael Ignatieff, old friends of Rieff’s whose blurbs grace the cover, but the arguments within aren’t meaningfully distinct from the toxic bigotry of Trump-aligned demagogues like Chaya Raichik (the notorious, Elon Musk-endorsed hatemonger who doxxes trans people under the social media handle Libs of TikTok, whose output has inspired at least 21 bomb threats, and whose posts Rieff frequently promotes or positively interacts with on his Twitter account).

In July 2025, Rieff signed the Manhattan Institute Statement on Higher Education, authored by the influential anti-woke activist Christopher Rufo, which called on President Trump “to draft a new contract with the universities, which should be written into every grant, payment, loan, eligibility, and accreditation, and punishable by revocation of all public benefit” that would totally ban DEI in higher ed and impose draconian measures in order to “push back the forces of radicalism and create the space for real knowledge.” Rieff was arguably the most left-leaning signatory on a list that also included Jordan Peterson, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Yoram Hazony, and Ben Shapiro, among other prominent conservatives. In an interview in December, Rieff told me that the decision to sign the Rufo letter was a “60-40 judgment call.” “I thought the statement was very poor, and I told Rufo that,” he said. “But I decided to sign it anyway, because I agreed with enough of its critique of the universities that I was willing to attach my name to it.”

Rieff is far from the best known or most consequential writer of the Trump era, but he does signify something beyond himself. The genre of mid-twentieth century intellectual liberalism that has profoundly shaped his life now faces a prolonged and possibly terminal crisis. After a kind of extended adolescence spanning the Cold War decades and spent very self-consciously in Sontag’s shadow, Rieff came into his own as a writer at the proverbial End of History, finding in Sarajevo a new purpose for humanitarian ideals that at the very least was legible to liberalism. But Rieff never identified with liberalism himself; by his own account, he has always been a pessimist and an anti-utopian by nature, and the tumultuous events of the past three decades would only deepen his alienation from and ultimate disgust with liberalism. Today he sees liberalism, or more precisely the traditional left- and right-of-center parties of the developed West, as offering “no answers to any of the fundamental questions of our time”—he lists climate change, global mass migration, artificial intelligence, the collapse of the middle class, and the crisis of education—and argues that “if a political system has no answers, frankly, it deserves to disappear.” It’s a bleak diagnosis, but one that appears to be ever more widely shared.

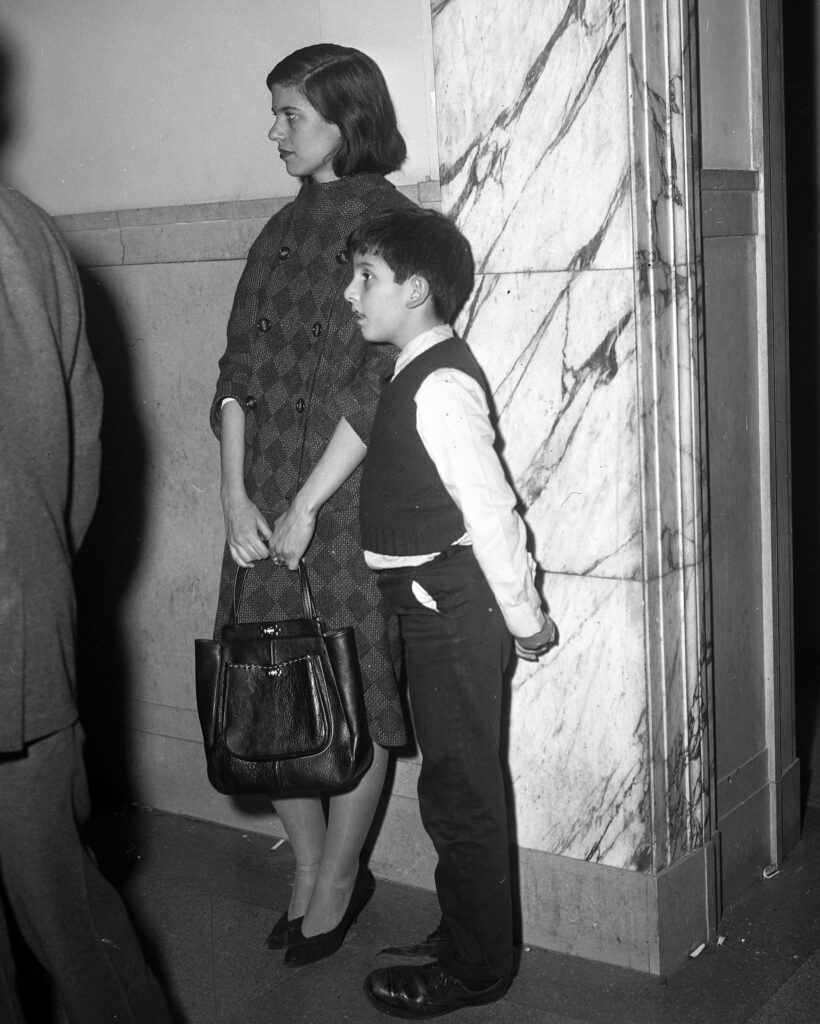

David Rieff was born and initially raised in New England, where his father taught at Brandeis while his mother took graduate courses at the University of Connecticut and then Harvard and had a social circle that included Susan and Jacob Taubes and Herbert Marcuse. The marriage was not a happy one—Sontag would later describe Philip in her journals as “an emotional totalitarian”—and by the time David was five he was living with his father in Berkeley while Sontag studied at Oxford and then Paris. By the beginning of 1959, they were divorced, and Sontag settled on the Upper West Side. David was expected to grow up bicoastal, spending summers in California, but in 1961, Philip unsuccessfully sued for custody, stalked Sontag and attacked her in the press, and in particular targeted her for her romantic relationships with women. All of this backfired, his visitation rights were reduced, and from age 10 David was raised primarily by Sontag and her extended social network.

In Benjamin Moser’s Pulitzer-winning 2019 biography of Sontag—more on which further down—David’s upbringing comes across as a curious mix of intense intellectual mentorship and neglect. Though by all accounts Sontag dearly loved David, she struggled as a single mother in New York, and David struck her many friends and lovers as isolated, unhappy, and curiously interested in weapons. Sontag raised him on Voltaire, Homer, and Tolstoy, and would boast that he was “the second-greatest mind of his generation” while he was still an adolescent. At the same time, she would often ignore him or leave him with friends during long sojourns in Europe; as a teenager, he was free to travel with friends unaccompanied by adults to Pakistan or Peru.

“Philip Roth told me that I come from an intellectual somewhere, but a geographic and ethnic nowhere,” Rieff told me. “But I do come from an ethnic somewhere, and that’s lesbian America. I grew up surrounded largely by gay people in my childhood in New York.” He was raised by the city’s queer literary bohemia, including by his mother’s friends during her frequent absences.

A blend of freewheeling curiosity, obsessive interests, and career aimlessness followed Rieff into early adulthood. He dropped out of Amherst after his freshman year, worked for the radical priest Ivan Illich in Cuernavaca, Mexico (where he learned fluent Spanish, commencing a deep and ongoing relationship with Latin America), and spent nearly two years as a New York City cabdriver before Sontag pressured him to enroll at Princeton, where he was an indifferent and disengaged student. Significantly older than his fellow undergrads, Rieff spent much of his Princeton era in Manhattan—in part to take care of Sontag, who endured breast cancer for the duration of his studies (aided by considerable donations from wealthy acquaintances like New Republic publisher Marty Peretz), an experience that would inspire her book Illness as Metaphor.

It was in these years that Rieff began, according to multiple family friends interviewed by Moser, to cultivate a persona as a kind of curmudgeonly intellectual aristocrat, a combative, snobby enfant terrible whom Sontag was grooming for an inherited role in the New York literary scene even before he graduated in 1978. Right out of college, Rieff was hired by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux and became his own mother’s editor, extending an already toxic dynamic. He continued to live with his mother on Riverside Drive, and when she moved downtown, he moved in next door. In 1982, at age 30, Rieff suffered a mental breakdown, a brush with cancer, a breakup, and an escalating cocaine addiction that negatively affected both his work and his relationship with Sontag, who fled the scene for Italy with a lover. Rieff spent the next six months in the care of his friend Jamaica Kincaid and her husband Allen Shawn.

But over the next decade, Rieff largely pulled himself together. He quit drugs, left FSG at the urging of his mother’s literary agent Andrew Wylie, and embraced a career as a writer, which he had long feared doing. “I was too arrogant. I thought somehow I should be spared the fact that for the first ten years of any career I would make, the first line would be ‘David Rieff, son of Susan Sontag,’” he told me. “Finally, I gave myself a kick in the ass and said, so what?” He published a well-received book about Miami in 1987, another about Los Angeles in 1991, and a follow-up about Miami in 1993—all of which drew upon his experiences in Latin America and presciently situated two of North America’s fastest-growing cities in a hemisphere increasingly shaped by transnational immigration flows. In September 1992, months into the Serbian bombardment of Sarajevo, he traveled to Bosnia to see one of the biggest stories in the world for himself. There, as the seemingly predictable world shaped by the Cold War unraveled into ethnonational chaos, 40-year-old David Rieff finally found an animating cause.

Slaughterhouse: Bosnia and the Failure of the West, the 1995 book that emerged from Rieff’s reporting, seethes with righteous anger. Rieff bears witness to the mass murder and expulsion of Bosnian Muslims and the collapse of what had once been a peaceful and cosmopolitan city. He is unsparing in his contempt for the Western liberals who stood by and let it happen. The book opens: “This is the story of a defeat,” and it closes: “The defeat is total, the disgrace complete” (a subsequently written afterword argues there was still more defeat and disgrace to come). In between, Rieff’s rich, detailed observations buttress a polemic in favor of humanitarian interventionism and the cause of a free and independent Bosnia-Herzegovina, a society built around multiculturalism and tolerance. “Bosnia was and always will be a just cause,” he proclaims. “It should have been the West’s cause. To have intervened on the side of Bosnia would have been self-defense, not charity.”

In his own account, confronting not only Serbian inhumanity but also international passivity was radicalizing for Rieff. “To return to the life you led before you have been to a scene of slaughter and bloodshed, at least if you are a citizen of the rich world, is to choke on the cant and the complacency of everything that used to be familiar and pleasurable to you,” he writes, adding, “traveling back and forth from a place like Sarajevo or Banja Luka to a place like Manhattan removed me from my friends and my past to a degree I had never dreamed possible. I felt not only as if I had returned from the land of the dead, but as if I too had become posthumous.”

Be that as it may, Slaughterhouse was favorably received back home, and Rieff—along with his mother whom he brought to Sarajevo in 1993, though her high-profile appearance may have upstaged his much more extensive engagement—can be credited with helping to develop the moral urgency that eventually led the Clinton administration to intervene in Bosnia and then in Kosovo. Rieff is cited by name in the conclusion of Samantha Power’s influential, Pulitzer-winning 2002 book A Problem From Hell, which catapulted Power into the position to lobby for US interventions in Libya and Syria a decade later (Though in a 2005 interview, Rieff warned that while Power’s intentions were admirable, her book represented an “argument for endless wars of altruism”).

The same year as A Problem From Hell, Rieff published A Bed for the Night: Humanitarianism in Crisis, which collects a decade of reporting from conflict zones around the globe, and was named one of the top books of 2002 in multiple national publications. Picking up where Slaughterhouse left off with the siege of Sarajevo and winding down with the 9/11 attacks, A Bed for the Night is a work marked by idealism giving way to pessimism. After cataloging more atrocity and more fecklessness from humanitarian agencies like the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and Médecins Sans Frontières, Rieff seems burned out and unsure of his own instincts. “Only in the Balkan wars, where, uniquely in my experience of such conflicts, I believed it was not just possible but imperative to take sides, was I confident enough about my political opinions to move from being a writer to being an activist,” Rieff writes.

Unlike some of his liberal interventionist peers, Rieff unequivocally opposed the invasion of Iraq. In a Charlie Rose appearance in 2002, he expressed skepticism of democracy promotion by force on a panel that also included the fervent Iraq War-supporter Christopher Hitchens; Rieff would later call the Iraq misadventure “that evil and pointless war.” He traveled to Iraq twice in the first year of the invasion and documented the catastrophic occupation for The New York Times. In a July 2003 afterword to the paperback edition of A Bed for the Night, Rieff seems even more disillusioned by the ways in which the rhetoric and the functional imperatives of humanitarian interventionism were used to justify the invasion, launched months earlier. “After Iraq, it is really no longer possible to imagine that [Bernard] Kouchner’s droit d’ingérence, the prospect of UN-sanctioned humanitarianism and human rights interventions, or the idea that military force will be used to ‘guarantee’ to humanitarians the right of access to conflict zones can mean anything other than the recolonization of the world,” he concludes. “No longer possible, but no more bearable for that.”

In his 2005 follow-up At the Point of a Gun: Democratic Dreams and Armed Intervention, Rieff expands on his skepticism for the exact kind of humanitarian interventionist wars his initial experience in Bosnia had led him to voice support for. From firsthand experience with the world’s most despair-inducing crises, he had evolved into a nuanced critic of the gulf between humane intentions and imperialist outcomes. Sooner, and with better-informed insights, than many of his friends in the liberal intelligentsia, Rieff had grown disaffected from Western triumphalism and its utopian promises at the end of the Cold War.

His focus, at any rate, was turning inward, toward the personal. In 2004, Sontag died at 71, nine months after she was given a fatal diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). She had survived cancer before, and her subsequent Illness as Metaphor had rejected the kind of magical thinking Rieff would nonetheless observe from her—to the point of outright denial of the terminal nature of her condition, which Rieff felt compelled to lie to her about—as she was devoured by MDS. Rieff’s memoir of his final months at her side, Swimming in a Sea of Death, was published in 2008 to strong reviews. It was in immediate tension with the memoir Annie Leibovitz, Sontag’s longtime if unacknowledged romantic partner, had published two years prior, which appalled Rieff by including photos of Sontag in the advanced stages of her illness. Rieff and Leibovitz had a terrible relationship, and per Moser, “Many of those who had accompanied Susan in her last months found David’s account dissembling, and many of those who distrusted Annie found her images of Susan’s suffering obscene.”

Like so much of Rieff’s writing on international affairs, Swimming is marked by ambivalence and fatalism, with much attention given to the author’s struggles over whether to indulge his mother’s illusions about her own odds of survival, and by the deep stresses in their relationship that were exacerbated toward the end. “I still cannot believe there was nothing I could do to help,” he laments. The horror of a loved one’s mortality, like the horrors he has witnessed overseas, is matched by a sense of powerlessness and irreducible regret. “Viscerally I do not believe that my mother could love a world without herself,” Rieff writes.

Perhaps burdened by so many painful memories, Rieff would come to rebel philosophically against memory itself, with the publication of Against Remembrance in 2011 and In Praise of Forgetting: Historical Memory and Its Ironies in 2016, both of which argue against the post-Holocaust logic of “Never Forget” that Rieff himself had been associated with in the 1990s. Reflecting on Bosnia—“which was in large measure a slaughter fueled by collective memory, or, more precisely, by the inability to forget”—and so many other places where he had seen historical resentments abused to justify new atrocities, Rieff argues for almost a literal End of History. As he concludes, “without at least the option of forgetting, we would be wounded monsters, unforgiving and unforgiven… and, assuming we have been paying attention, inconsolable.”

Rieff spent the first 40 years of his life, and the bulk of the Cold War, in his mother’s shadow, a brilliant but undisciplined thinker whose education, career, home, and personal life were all shaped to a smothering extent both by her many gifts—intellectual and financial—and her interpersonal shortcomings. With the Cold War’s end, as he ventured out to the most benighted corners of the world, he found his own voice and enjoyed a measure of success chronicling both the promise and the bitter reality of a vision of universal human rights and global governance. But in his personal life as in geopolitics, gravity reasserted itself. He could not escape Sontag’s legacy any more than the rest of the world could escape its own bloody history.

As custodian of that legacy and the vast trove of personal papers that made it up—including several volumes of her diaries that he published posthumously—Rieff made the fateful decision to entrust their interpretation to Benjamin Moser, the scholar previously best known for his role in translating the works of the Brazilian novelist Clarice Lispector into English. Moser and Rieff initially hit it off, but well before the publication of Sontag: Her Life and Work in 2019, their relationship had soured. Moser’s exhaustively researched biography, though acclaimed and awarded, contained much material that infuriated Rieff, not only documenting the worst moments of his own life and the least flattering details of his mother’s, but also including a bombshell allegation against his late father, whom Moser portrays as a pompous intellectual fraud and thoroughly unpleasant figure. In Moser’s account, Philip Rieff’s first and arguably most influential book, Freud: The Mind of the Moralist (1959), was in fact largely written by Sontag—a claim possibly substantiated by the elder Rieff’s inscription in Sontag’s copy: “Susan, Love of my life, mother of my son, co-author of this book: forgive me. Please. Philip.” (Though Moser’s argument is not universally accepted, and was criticized by Janet Malcolm in The New Yorker among others, there is wide agreement that Sontag made significant and uncredited contributions.)

Rieff bitterly regrets approaching Moser, though he acknowledges Moser’s intelligence. “As I got more and more to understand what he was up to, I had graver and graver reservations,” he told me, adding that he considers the resulting biography “a travesty.” Among Rieff’s grievances are Moser’s criticism of Sontag for never coming out as a lesbian (as Rieff notes, her sexuality was significantly more complex and her generation had a complicated relationship with the closet); Moser casting Sontag as a ruthless and cynical climber and careerist while neglecting the substance of her work (the book does, in fact, engage extensively with her work); and, of course, Moser’s harsh portrait of Philip Rieff.

“David had literally years to read and comment on my book,” Moser told me when confronted with these objections, in his first public statement on Rieff since the book’s publication. “I had no motive to offend him. If he took offense at things I wrote, he could have tried to work with me rather than trashing a book he admits he hasn’t read.”

For the past decade, Rieff has contributed prolifically to magazines on multiple continents—increasingly in heterodox, anti-woke, or at least pre-woke publications like UnHerd, Compact, and Enrique Krauze’s Spanish-language journal Letras Libres. He has spent extended stretches of time in Buenos Aires, and since April 2022, just months into Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, he has also taught regular classes at Kyiv-Mohyla Academy and at least occasionally visited the front lines, still drawn to war zones even in his eighth decade. At a speech at Kyiv-Mohyla in September 2024, which was republished in these pages, he said that he subscribes to Catholic just war theory and believes that Ukraine’s struggle to defend its territory is the only truly justified war he’s witnessed since Bosnia 30 years ago.

Desire and Fate, published in late 2024, is Rieff’s first book from this period, and his first book that was originally written online, in short and ephemeral essays published in many cases at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. It showcases a very different Rieff than any of his previous work might suggest—a Rieff singularly fixated on the tyranny of wokeness. In a September 2025 interview with El Mundo America promoting the book, he calls wokeness (or “wokism” in some cases) “a deadly danger to high culture,” “a moral justification to abandon the working class,” “a deep rejection of the idea of destiny,” and a product of “a completely self-absorbed country [the United States], giving narcissism a bad name.” He denounces the work of Judith Butler, the leading theorist of gender as a social construct, as “one of the great frauds of our time. It’s like phrenology!” The pieces that make up Desire and Fate strike a similar tone of perpetual grievance; again and again, Rieff bemoans “woke” student activists whose embrace of identity politics is an affront to civilization, a travesty of Western culture, and, particularly where transgender advocacy is concerned, an assault on empirical reality itself.

The writings of Ibram X. Kendi and Robin DiAngelo, the cancellation of Philip Roth biographer Blake Bailey over his grooming of high school students, trigger warnings at Oberlin… it’s all in Desire and Fate, and you’ve heard it all before. Little of what Rieff is saying about the present culture wars is new or unique to him. In a podcast interview in April 2025, he acknowledged his support for the Trump administration crackdown on “wokeness” in higher education, though he is not a Trump supporter on balance (he objects in particular to Trump’s efforts to weaken NATO and undermine Ukraine’s war effort). Rieff also favorably cites the critic Wesley Yang, who coined the term “successor ideology” to describe wokeness, and whose social media feed for the past several years has been an obsessive barrage of transphobic invective. In our conversation, Rieff further cited the anti-identitarian Marxist critic Adolph Reed, arguing—as many others have—that because “wokeness” lacks any materialist critique, it is easily co-opted by capitalism and will succeed mainly in destroying high culture, leaving behind a society organized solely around money.

Desire and Fate is mostly notable for who wrote it, and for how Rieff draws on the works of both of his parents to buttress it. Expanding on his father’s The Triumph of the Therapeutic (1966), he declares wokeness “the triumph of the traumatic,” accusing today’s youths of claiming to be traumatized by disagreement and weaponizing their supposed traumas to shut down dissent (“This is not a revolution, it’s a tantrum.”). Philip Rieff was an infamous reactionary in his later academic career, a prophet of cultural and civilizational decline—as Moser notes, he refused to take on women as dissertation advisees, referred to homosexuals as “disgusting,” and panicked about hip hop. A Freudian reading seems all too appropriate here: one senses in Desire and Fate that the younger Rieff is embracing the aggrieved and frustrated worldview of his mostly absent father.

From his mother’s Illness as Metaphor, as Lee Siegel argues, Rieff draws his critique of ever-expanding definitions of “health” that are used to justify, among other things, medical gender transitions. I asked Rieff if his fixation on gender transition has a personal origin. At first he demurred, but then he noted his upbringing surrounded by often radical lesbians. “What I remember vividly was that all these women are trying to get away from penises,” he recalled. “And here come the trans people, at least the radical side of them, saying genitalia doesn’t define your gender identity or even your sex, that a lesbian should be willing to date a trans person with a penis. If I’m playing vulgar psychoanalyst of myself, that’s an element.” This anxiety—that people with penises who identify as women inherently violate and terrorize all-female spaces—is a familiar trope employed by what are often termed “Trans-Exclusive Radical Feminists” or TERFs, a term that has come to be used disparagingly against all transphobes. Rieff clarified that he did not inherit this fear from Sontag, who certainly had sexual relationships with men, but he attributes it to the wider milieu around her. It’s a plausible-sounding origin story for a prejudice that has in recent years come to be a common entry point to the illiberal right.

This past fall, Rieff appeared at an Open Society-supported confab of leading liberal intellectuals, including Leon Wieseltier, Paul Berman, and Enrique Krauze, in Mexico City—a revival of a 1990 gathering hosted by Octavio Paz and attended by departed luminaries like Daniel Bell, Irving Howe, Czesław Miłosz, and Mario Vargas Llosa. In the account of his fellow panelist Celeste Marcus, the executive editor of the Wieseltier-founded quarterly journal Liberties (to which Rieff has contributed an article about the failures of Peronism in Argentina), Rieff remains centrally concerned with the global menace of authoritarianism and illiberalism, which he perceives everywhere from Vladimir Putin’s Kremlin to Donald Trump’s White House.

Yet he seems to recognize the fashions of campus social justice activism as a parallel menace, one that Trump’s own allies on the right are making, in his view, commendable efforts to defeat. The Rieff of Desire and Fate may contain contradictions and he may profess to be unbound by ideological categories, but compared with his earlier work there’s a curious flattening of his affect, an aversion to what was once characteristic ambivalence. Having once condemned the West for its failure to protect innocent lives and the hollowness of its professed ideals, he now positions himself as a defender of Western civilization on both the metaphorical battlegrounds of high culture and the physical battlegrounds of the Donbas. Having once urged the forgetting of history, he now recoils at undergraduates who want to tear down statues and the established narratives they represent. The endless compassion he has shown for the wretched of the earth is now matched by a seemingly bottomless contempt for anyone in the developed world who makes any claim of marginality or oppression at all.

Rieff is not alone in these fixations; as I’ve previously written, some of them appeared in the pages of Liberties, in more widely circulated publications like The Atlantic and The New York Times, and online in the newsletter Persuasion and of course Bari Weiss’s The Free Press, among many other outlets over the course of the Biden years. “Wokeness” does broadly represent a set of commitments that have been received as hostile to much of what constituted mainstream liberalism a generation ago, at the moment of its greatest hegemony after the collapse of communism and before the present crisis. But whereas most of the above outlets, with Weiss’s as a notorious exception, have generally stood up for the speech rights of the “woke” against Trump’s federal assault over the past year, Rieff remains at least as unsettled by wokeness as by the Trump administration.

Social media and its perverse incentives have only exacerbated this sense of threat—and for a writer in his 70s, Rieff maintains a noticeably busy account on the platform that has been called X since Elon Musk acquired it in 2022 and promptly began directing its algorithm to amplify transphobic hate speech and the accounts of outspoken transphobes like J.K. Rowling and Graham Lineham, both of whom Rieff has repeatedly promoted. In a representative sample of his innumerable recent tweets on the topic, Rieff has denounced “the trans psychosis,” “the trans madness,” and “the trans ideology,” and asserted that “trans is a religion.” “I think it’s an addiction,” Rieff told me, referring to his Twitter habit, which he compared to a weakness for Doritos. “I don’t exactly think better of myself for all the time I spend on Twitter.” When I asked if he thinks it’s affected his thinking, he replied “God, I hope not, but it probably has.”

The values 1990s liberalism stood for—unabashed individualism in culture, unfettered capitalism in economics, and an expansive humanitarianism in foreign policy—have faced sustained challenges on every front, and those intellectuals whose careers flourished at the End of History have largely struggled to articulate what liberalism ought to mean in the twenty-first century. In the inaugural issue of Liberties, Wieseltier himself has offered one possibility: “a large heart, a generous heart, a receptive heart, an expansive heart, an unconforming heart, a heart animated by a wide variety of human expressions.”

It’s a definition Wieseltier’s longtime friend Susan Sontag might have recognized as well, at least in her later decades, but Rieff rejects it for himself, and stressed to me that he has no real interest in defending liberalism at all. “There is an argument that could say that objectively, to use the old Marxist boilerplate, you’d have to put me on the right. But I don’t even feel that. I just feel I’m a cultural pessimist,” Rieff told me. “Civilization waxes and wanes, and I think ours is pretty much finishing up. Whatever succeeds it, it certainly won’t be Western liberalism.”

David Klion is a columnist for The Nation, a contributing editor at Jewish Currents, and a writer for various publications. He lives in Brooklyn and is working on a book about the legacy of neoconservatism.